Heritage — do we really need this burden in the 21st Century?

- CRIAAS Nashik

- Sep 11, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 26

By Vedang Joshi and Prachi Pol

“Heritage,” according to the Collins Dictionary, is defined as “the rights, burdens, or status resulting from being born in a certain time or place.” This includes everything from your genes to your favourite pair of jeans. It gives us a sense of identity and belonging. However, is heritage treated with the respect it deserves or is it seen as a burden? Do we need another load to add to the multitude of challenges and burdens that come with living in the twenty-first century? Why would the government spend our scarce resources on these ruins? Let’s dig a little deeper into these concerns.

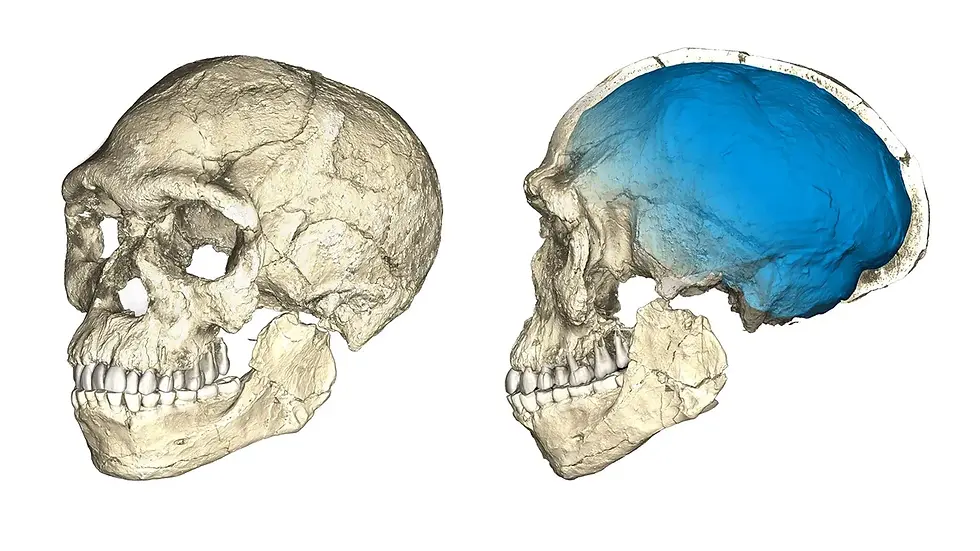

To start, heritage is a huge horizon of objects, cultures, traditions, locations, and rituals that are directly related to your current way of life. According to Yuval Noah Harari, the capacity for effective communication, or as he prefers to call it, “the gossip,” could be all that separates modern humans from other extant hominid species. Eventually, this “gossip” became information, and with the addition of experience, it became knowledge. This knowledge is passed down from one generation to the next in the shape of culture, values, customs, and rituals. And this vast repository of information, that has shaped who we are, is referred to as Heritage.

In the current age of AI and IT, the word “legacy,” which has a similar connotation, is more frequently employed. The term legacy in the context of computers or AI simply refers to features acquired from prior versions. It is the duty of the developer to retain the greatest features in the legacy mode so that they can be improved upon by upcoming hardware and software generations. Similar modest and steady changes have been made by the estimated 3,00,000-year-old human legacy. It is now our duty to preserve, protect, and pass this legacy to our upcoming generations.

In order to make research easier, our heritage is divided into tangible and intangible elements. All inanimate objects that can be touched or handled physically are considered to be part of tangible heritage. It resembles a device’s hardware. While intangibles are more like software inside a machine. These include intangible elements like traditions, rituals, recipes, etc. Both aspects are equally crucial for a society’s overall functioning. However, an individual or a group of people cannot accomplish this on their own. It is at this point that democratically elected governments enter the picture. “We the People” elect any government with a specific agenda that has something to do with improving our daily lives. In fact, because it is a natural part of who we are, culture and subsequently heritage play a significant role in day-to-day life. All local, national, and international governing bodies have different establishments for preserving, conserving, and passing on the Human Legacy to future generations. These groups are largely decentralized to facilitate governance. Let’s explore it further.

At a global level, the United Nations Education, Science, and Culture Organization (UNESCO) is a distinct entity for global cultural activities. UNESCO monitors both tangible and intangible aspects of global heritage. They conserve, record, preserve, and revitalize local heritage elements with “Universal Value” with the assistance of local government bodies. However, it has its own limitations. Since not all heritage practices, monuments, or other components can be monitored by UNESCO, national and local governments must step up.

National Level — Almost every nation has a Ministry of Culture, which plans and executes heritage-related activities. Take India as an example. There is a Ministry of Culture, and under it are various directorates like the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, (IGNCA) the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and the Anthropological Survey of India, among others. These directorates, with each other’s help, track down tangible and intangible heritage elements and preserve, conserve, restore and showcase the specific elements with National Importance. ASI works on identifying, locating, and protecting Archaeological Heritage sites through its 34 circles. Despite being a central agency, with such a large number of sites and structures in India, the Central government only protects and manages a small number of structures or sites. Other directorates, such as the National Mission on Manuscripts (NMM) and the National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities (NMMA), have a large volume of databases related to their respective work areas. Although this appears to be a comprehensive work, there are numerous gaps, such as an insufficient workforce, a lack of access to specific sites or antiquities, and a variety of other factors. As a result, we must further localize the control.

At the state level, nearly every Indian state has its own Archaeology and Museum Directorates for the management of Tangible Cultural Heritage, which may not be of National Importance but are unquestionable of Regional Importance. Some states, such as Maharashtra and Gujarat, have a language ministry that is solely responsible for managing and promoting the state’s linguistic heritage. These ministries, despite governing a relatively small area, have their own set of constraints. This is where the District committees come in. Despite this, district committees monitor and report damage/s to heritage sites or practices to the state or central governments without any rights of their own. Unfortunately, only a few districts in India have active heritage committees.

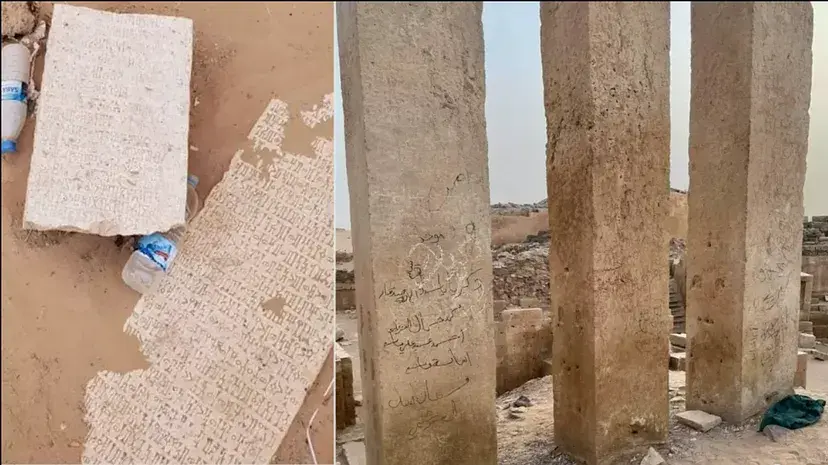

This is just one of many causes for why heritage vandalism is such a big issue. In our society, the issue of vandalism has become commonplace. Despite the fact that vandalism is wrong and punishable, it frequently comes up in casual conversations. In India, heritage vandalism is seen almost everywhere, from burning down government property to damaging monuments under the guise of protest. Vandals use buildings, roads, and monuments as signboards, proclaiming their love or using it as notice boards or as a canvas for art through graffiti, and it has become an essential part of India’s rich heritage. The context of this vandalism can be linked to a variety of issues from psychology, societal anxiety, vendetta, love, friendship, profanity, and religious or political movements.

Irrespective of the context or motivation for these acts of vandalism the loss of heritage or the damages to these knowledge repositories is eminent. For global reference purposes, let us look at the case of Afghanistan. The 2 large standing Buddhas that were carved in the valley of Bamiyan approximately 1700 years ago were pulled down. In March 2001 the Taliban government militia demolished these colossal statues. A similar case can be seen in Yemen as the heritage structures became vulnerable due to war conditions. These and many more examples are evident enough to strike a serious conversation about the detachment of this generation from their roots.

India is not indifferent to these situations of vandalism of heritage structures. Indian heritage has suffered enough in the name of religious outrage, political instability, communal violence, insensitive misguided youth, and the list can go on. A glimpse of destruction in the temples of south India in the last 10 years is recorded by Mr. Ameen Ahmed. In his blog, he maps the vandalized temples and the level of destruction. Even heavily protected sites like Golkonda are not safe from these vandals. Vandalism at any site, monument, or public property is a punishable offense under IPC section 425. But, are legal and criminal measures alone sufficient? Is this ever enough to deter offenders? The obvious answer is NO; laws will always have loopholes, and offenders are experts at exploiting them.

It is instead the responsibility of civilians like you and me to safeguard the Human Legacy. It is our responsibility to protect them from harm. The heritage sites can be largely saved for future generations by two simple actions that we, as citizens, should take. First and foremost, refrain from engaging in any type of vandalism, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Furthermore, it is necessary to sensitize the public at large about the culture and heritage of our country. And this is only possible if heritage enthusiasts like you and me come forward and spare some time to get people to understand the importance of the cultural identity of our country. With the collective strength of the public’s efforts and the government’s penal actions, we cannot guarantee the safeguarding of our heritage. However, it will have a significant impact if these attempts are well-supported and consistent.

Comments